A Three-Part Blog Series By Julia Yanker

Photos | Julia Yanker and Steve Fassbinder

The first article in a three-part series about how to recover our mental edge after a scary swiftwater incident - the repercussions of which are referred to in the wilderness first responder community as “stress injury”.

Sitting in my packraft, I reached the bottom of the wave. I couldn’t see anything of my partner, his paddle, or boat at the bottom of the next swell. The water was huge; a towering wave train of brown murkiness.

We had no business being on this river at high water, having only gone boating a handful of times. After an exhilarating ride down a half mile of wave train with as much or even more ahead, a rogue lateral came out of nowhere and flipped me out of my boat. As my head came above water, I made a rookie mistake as I pushed my boat away from me, thinking two hands for swimming were better than one. Within a few more seconds, the only thought in my head was, “I need to get out of this river or I’m going to die.”

As packrafters, we’ve all been in that same situation: swimming, when we had not expected it. Some swims are benign, even fun, where we surface smiling, and we laugh after we’ve hauled ourselves back into our boats. But sometimes, they leave us shaking and panting, coughing up water and realizing how close we’ve come to a fatal drowning. The river is full of risks that we attempt to mitigate, but it is inevitable that eventually we will find ourselves in a scary, life-or-death situation; perhaps swimming, pinned against a rock or tree, or witnessing someone else’s emergency.

After my swim, I found myself in a position many other boaters have found themselves in: feeling a hesitancy and anxiety about getting back on the water. In this 3-part series, we will explore stress injury for adventurers - how and why it happens, as well as how to recover.

Stress Injury: What is it?

Psychological stress injury is when we experience a stressful event that overwhelms our nervous system’s ability to cope with it; “too much, too soon, too fast” is how some characterize this mental trauma. It occurs with events our nervous system perceives as dangerous - whether the danger is real or imagined. As adventurers who participate in many outdoor activities, the chance that we will find ourselves in one or more of these situations is high. In fact, the accumulated burden of multiple traumatic events can eventually cause the person to show symptoms where there had been none before. However, not everyone experiences stress injury from a traumatic event. Let’s take a look at the mechanism of injury and why some people are more resilient to this stress than others.

It’s NOT All in Your Head: The Nervous System’s Threat Response Cycle

Let’s set the record straight on one thing right now: mental trauma, or stress injury, is not “all in your head” and something you should be able to buck up about, getting on with life by simply deciding to. It does not mean you are weak or something is wrong with you, and it is not a mental problem; it is a body problem. Yes, the symptoms of stress injury may seem mentally based, since many of the symptoms occur in the mind - anxiety, intrusive thoughts, nightmares, and flashbacks, to name a few. But the underlying cause of these mental symptoms is actually physiological, stemming from the nervous system’s attempts to keep you safe and alive. So while your prefrontal cortex might be saying, “Just shake it off and move on, silly!” The oldest parts of our brain (the brain stem, cerebellum, and limbic system) are sending signals that no amount of positive self-talk will likely reverse.

The Threat Response Cycle

To get a better understanding of how stress injury occurs and how to prevent it, it is necessary to understand how the body responds to a situation it perceives as threatening (because there is no difference in how the nervous system responds to an actual snake on the ground vs. a stick on the ground it thinks is a snake). Let’s get nerdy with it for just a few moments and dive into the science behind all this.

This entire process is governed by our autonomic nervous system, and as the name implies, this is an automatic process we have no conscious control over - like it or not. This is one of the oldest parts of ourselves and has been helping organisms survive for millions of years. Its primary job is to constantly scan our environment (using our 5 senses), looking for threats and then automatically and instantly responding to them as they are perceived.

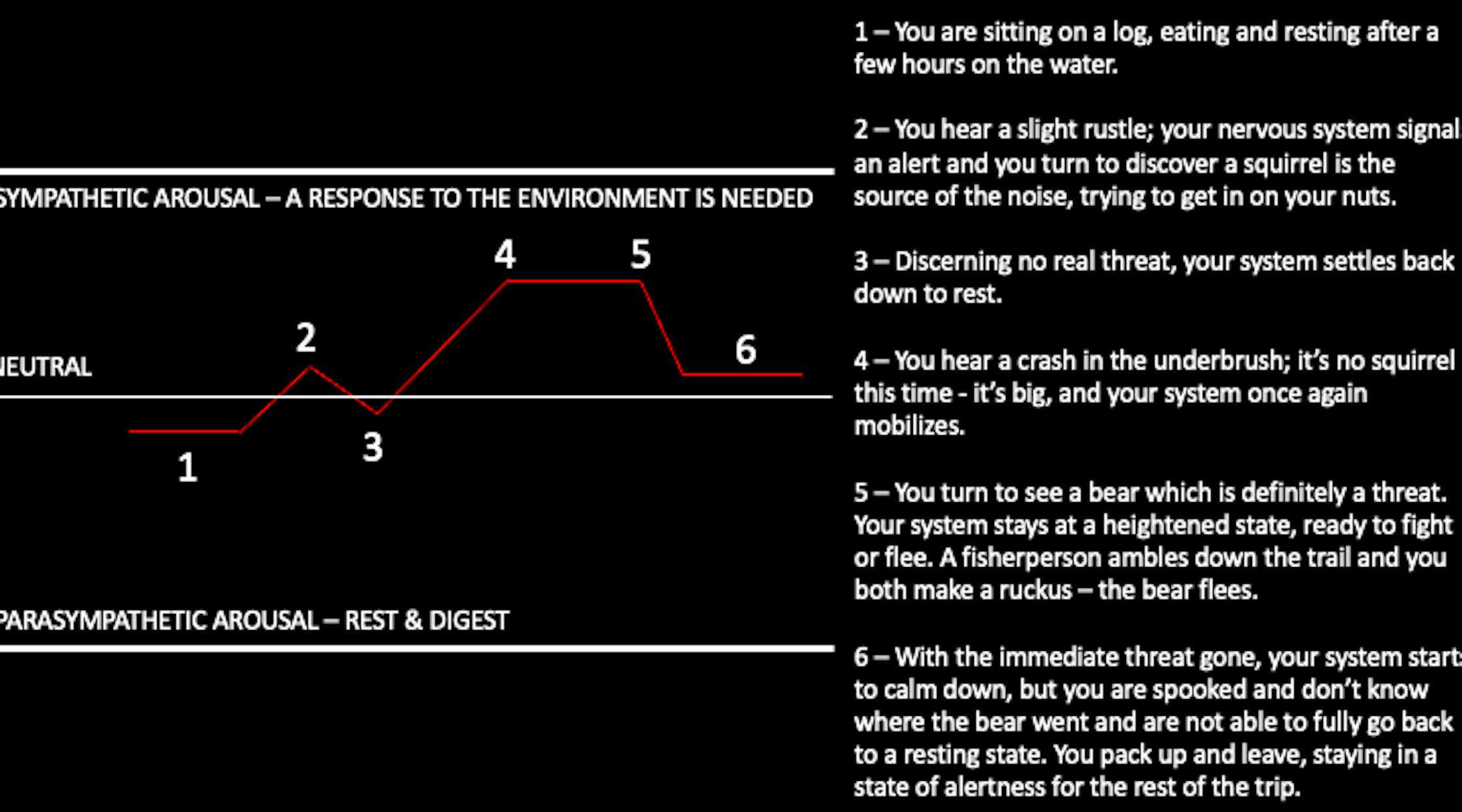

When there are no immediate threats in our environment, we relax and our nervous system goes into a parasympathetic response; also known as rest and digest. If there is a threat or other environmental stimulus that requires our attention, a sympathetic response is activated. The illustration below explains it:

So, when that rogue lateral came at me and I suddenly found myself in the water, my sympathetic nervous system kicked into high gear by mobilizing an immense amount of energy to get me out of that dangerously high river alive. Nearly instantaneously, I was prepared to swim for my life as my blood moved from my organs to my muscles, while my heart and respiratory rate increased. My sympathetic system would continue to provide this energy as long as I needed it.

Within a few minutes, I found myself on shore. I walked downriver and reunited with my boat and companions. At this point, the energy my body had generated to save my life was no longer necessary, but there was still a residual amount left over. As I sat on the rocks, my body shook and trembled as the excess energy found release through these muscle tremors. My system slowly came back to homeostasis now that the threat had passed. I got back in my boat, and we arrived without further incident at the take out.

What Comes Up Must Come Down

Once our body begins the threat response cycle by generating energy to respond to a threat, the system is designed to complete the energetic cycle by dispelling it - either using it up in the defensive response, or discharging it some other way once it is no longer necessary. This discharge often looks like shaking/trembling, twitching, crying, anger/rage, or heat. When this energy does not get discharged, it stays in the body, like a coiled spring, waiting to complete the cycle and discharge that energy once it is triggered some other time. The next time you are in a situation similar in some way to the original situation, this residual energy will get activated and our bodies will again find themselves with heightened levels of activation that do not seem to fit the needs of the current situation. For instance, I might be driving down the road by that whitewater section and find my body responding as though I were back in the water, swimming for my life, all over again. This is where stress injury, or trauma, comes from.

Dr. Peter Levine describes this process and how to heal from it in his work with a technique called Somatic Experiencing®. In the early days of researching this phenomenon, he asked the question, “Why don’t wild animals, who experience life or death situations frequently, have PTSD?” He found that the answer was simple: wild animals complete the threat response cycle by discharging the excess energy. Humans, meanwhile, with our highly developed prefrontal cortex, have the ability to override the completion of this cycle with our thoughts and actions. When the urge to tremble or cry comes upon us, we might respond with, “I shouldn’t cry in front of my friends,” or “this trembling is weird, I don’t want anyone to think I’m a wuss,” and we interrupt the cycle and move on with our day.

In Part II of this series, we will explore psychological first aid and how to avoid walking away from a scary situation without the residual effects of stress injury. We’ll review how to recognize that treatment is necessary and how to apply it. This technique applies to all forms of trauma - whether acquired through boating, a climbing fall or bike accident as well as the broader situations humans find themselves in like car accidents, war, natural disasters, medical procedures, assault, birth trauma, etc. In fact, all these situations can pile on top of each other over time to eventually overwhelm our systems. Then, a relatively insignificant incident can trigger symptoms of trauma from something that occurred years ago - the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back.

My hope for you in reading Part I is multilayered. I hope to normalize and bring awareness to the physiological stress injury response, aka trauma - it does not mean you are weak or there is something wrong with you. Remember, it is a body problem, not a mind problem. You are responding to trapped survival energy in the body that needs to be released, and this energy has an impact on our overall well being - mind, body, and soul. Bad things happen. And while we cannot erase the memories or all the feels that are associated with them, we can lessen their impact so we’re able to enjoy our lives and continue to engage in the activities we love doing with the people we love doing them with.

About the Author:

Julia Yanker is an adventurer and Somatic Coach specializing in trauma resolution who has received 4 years of training in the technique of Somatic Experiencing®, a trauma resolution modality used around the world to help people heal from trauma. She lives in Bozeman, Montana, and jokes that she has participated in every adventure sport at least once (besides the ones that involve jumping off or out of things). She mostly spends her time packrafting, horseback riding, camping, foraging, and skiing. You can learn more about her work on her website or follow her on Instagram.