Paolo Marchesi on Fly Fishing in Remote Regions of Baja & Meeting Chewy, Former Mexican Gang Member-Turned Fisherman

A version of this article was first published in The Drake, “a magazine for those who fish.”

Story & photos by Paolo Marchesi.

I moved to Montana in 1999, tired of city living and after deciding to dedicate my life to fly fishing. As crazy as it sounded at the time, I became a “fly fishing” photographer. Eight years later I discovered surfing, and that’s how my Mexico life started.

In the winter of 2009, snow hammered Montana. I would shovel my way out of my house, and the following day I’d wake up to two more feet of the white stuff. After the 18th straight day of this, my hands and face frozen, yet dripping sweat, I started asking myself, “Why am I here?” Fly fishing and winter are not the best combination. Skiing didn’t seem as alluring as it used to be. Ice climbing and frost bites had left me with damaged feet and hands, and I could never keep them warm.

That year I put down the shovel, packed my camper, drove down to Baja to only come back when the snow melted. And that’s how it began.

Winters in Baja’s Fishing & Surfing Wonderland

I started spending my winters on the peninsula, leaving in December to come back for the Mother’s day hatch around the end of April. That was 2009, when the media pumped the news with how dangerous Mexico was.

“You are going where? Mexico? Are you crazy?” people kept asking me. In truth, if you didn’t look for blow in Tijuana at 2a.m., Baja was safer than most places in the United States. And the Baja rats like me kept it a secret and enjoyed the uncrowded surf breaks.

I mostly chased waves on the Pacific on my early trips to Mexico. Then one day I discovered halibut fishing. Before that, fishing the ocean seemed like a bummer deal. I thought you’d cast out as far as you could, just in time to watch a wave tumble your line back to you. If you were lucky, you’d step out, but most of the time it was a trap. You’d find yourself wrapped in your line, trying to figure out how to get out before the next wave came. It took me several years to realize that you have to fish the right conditions and places, and a whole new world opens up.

For halibut, I discovered that the sweet time is right between tides. Start fishing an hour before a change of tide and put down the rod an hour after. Any time outside of this window it would be slow, terribly slow, like zero fish. However during those two hours the fish would turn on. And, I wouldn’t just catch them, I would crush them.

People would say, “Oh yeah, Jonny caught a halibut four days ago, but we haven’t seen nothing since.” I quietly snuck into the water during the “honey time,” away from everyone. I’d pull out ten fish in a couple hours.

Not only was the action furious, but it was also very targeted, like fishing a river. I’d cast in shallow water, sometimes only inches deep, and tap little sandy spots among rocks and watch for the monsters to hit. I even had halibut take flies on top, in several feet of water. Aggressive predators, they’re an absolute blast to catch.

Fishing for Halibut made me interested in trying different spots and species of fish. Outside the usuals for Baja, like rooster fish or dorado, what about corbina, corvina, broomtail grouper, snappers, pargo or even snook?

I started fishing the many Lagoons, breeding ground for several species of fish and a place where larger predators like to feed. Particularly exciting, I never knew what I would hook.

Getting Away From It All… Or Not

Since 2009 many things have changed in Baja. Even though the media stopped talking about it, the crime rate in Mexico kept rising. By May 2018 we saw the highest murder rate in the history of Mexico. And this crime, unfortunately, has finally spread to Baja.

Unaware of this, tourists still flock to the peninsula, providing a more fertile environment for crime and a place for the cartels to do business. And suddenly, in Cabos San Lucas, one of the most popular destinations, someone found bodies hanging from bridges. In 2017, just in Cabos, 560 people were killed. However, the media tired of covering crime in Mexico, and so nobody hears about it. And the tourists keep coming.

Living in Baja, you start hearing of your neighbor being robbed at gunpoint or the bystander being killed during a cartel shooting. Suddenly you become more conscious of your surroundings.

Recently I started fishing more remote parts of Baja Magdalena. I mostly fished solo with my dog, Argo, and with the help of a 4×4 truck, an ATV, a packraft, and a tent. I theorized the more remote I’d go, the safer I would be.

However, I started hearing about more incidents even in remote areas. Fishermen from Mazatlan mainland had moved into the area, some to find better fishing, some to escape the crime of mainland, and some because they were criminals themselves. Locals like to call them “banditos.” Some of them started poaching, and unfortunately contribute to destroying this extremely delicate ecosystem. The fishing has declined dramatically in the past ten years.

I figured, I would go remote and get away from it all, but I was wrong.

In Search of Ever More Remote Spots

One day, several hours of narrow 4×4 hell roads took me to the drop off zone for my ATV. Then I traveled several miles by ATV along beaches undrivable by 4×4 vehicle. I then hid my tent and started my fishing exploration.

People told me about the fantastic opportunities in the mangroves, river-like channels chock full of groupers and other fish. However, the fishing wasn’t as red hot as I had expected. Some of the channels seemed to be void of fish.

The reason for the dearth of fish came to me in the form of a 22-foot panga with three fishermen on board. They had strung the opening of one of the rivers with a gill net and waited to pull it on a minus tide. The locals call this form of poaching doing a “Tapon” (putting a cap). They block the opening of these river-like channels right before a minus tide, and as all the water drains out, every fish has to swim into the net. It’s highly illegal as these channels are essential breeding grounds for the whole area, but this far away I am the only one to witness.

I chatted with many of the poachers, who approached me, curious to see a crazy Gringo in the middle of nowhere on a packraft. I carefully made sure to hide the location of my camp and ATV. Always had friendly conversations, as in truth these poachers are just poor people who don’t understand the long-term investment of protecting their fishing grounds. They didn’t look like criminals or banditos, and they all complained about how the fishing is not what it used to be. If only someone could educate them.

I still managed to find some deeper channels with more prominent outlets. All the places where a “Tapon” couldn’t happen and suddenly the fishing would come alive.

Meeting Chewy

During the explorations of a different part of Magdalena Bay, I ran into Chewy. As I tried to find a place to hide my camper, Chewy came out of nowhere waving me down. Wearing a pair of rubber boots and white overalls, he hollered in Spanish, “This way, this way!” He pointed at a place to park my camper near his camp. I didn’t realize I was so close to a small, remote boat launch. Chewy was the boat watcher.

Typically I would hesitate to reveal my location to a stranger, but Chewy seemed so warm and genuine. So I parked in his spot and made it my camp. Before I knew it, chewy dug out some steps so I could walk down the sandy cliff into the water, and he offered me one of the two fish he recently caught. His generosity kept pouring out, and next thing I knew I was eating oysters and scallops he shared with me.

I spent a day getting to know Chewy, and he overwhelmed me with his radiant personality. He lived in a makeshift tent, covered with a tarp, with no electricity or gas. He cooked with wood found nearby and ate the fish he caught, supplemented with small supplies the fishermen brought him. He made his tortillas and cooked delicious, simple meals with little and happily shared it with the rich Gringo.

The Man from Mazatlan Was Not a Crook

The next day he offered to guide me fishing with a Kayak, presumably some gringos had given him. I readily accepted his offer. What an opportunity to have a local guy who knew the area take me fishing! I was thrilled.

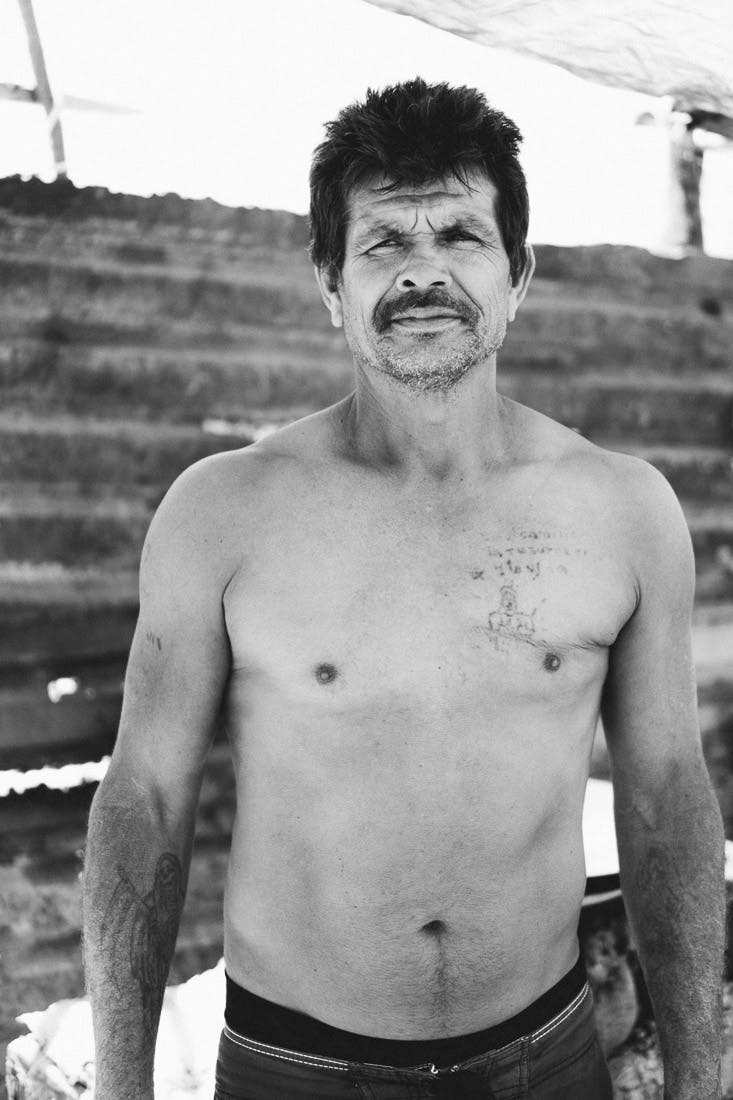

I inflated my packraft the next day, and we headed out. Chewy led with a powerful stroke. I had never seen him without long sleeves. Tattoos covered his lean, muscular arms–rudimentary designs, needle and ink homemade drawings, something you would expect done in a prison. Mexicans don’t wear tattoos to be hipsters. Usually, there is a connection with gangs, crime, or even the mafia.

“Just around the corner,” he kept telling me as he paddled further and further away from camp. I knew that some shady characters had moved into Magdalena Bay from Mazatlan, so I asked him where he was from. “Mazatlan,” he replied with a grin.

After we had been paddling for over an hour, we pulled out to a beach. Chewy encouraged me to cast from shore while he went looking for bait. He disappeared. I started feeling sick in my stomach, thinking what an idiot I had been. I pictured his buddies back at camp taking my camper, loaded with all my belongings–cameras, money, computer, hard drives, passport. In a panic, I grabbed the packraft and sprinted back to camp without waiting for Chewy to come back.

Before I had time to get very far, I saw him racing right behind me. “Where are you going?” he asked in Spanish.

“I am just worried for my stuff back at camp.” He looked at me, paused, and offered to go back and check on my stuff and told me to stay and fish. I sat with that idea in my head for several seconds and said, “Ok.” And I went back to fishing.

In those seconds, I decided that if my initial gut feelings for Chewy were wrong and he was indeed a crook, it would be too late. All my stuff would have disappeared by then. I might as well make the best of it.

I fished for a couple of hours. After catching a small snook and a pargo, I started my paddle back as the sun begun to drop over the horizon. In the faint evening light, as I approached camp, I could see Chewy crouched down on a hill, looking my way. My camper silhouetted by the sunset.

“At least they left my truck there,” I thought to myself. As I landed the packraft on shore, Chewy came running down to me. “I was worried for you, I was about to come and look for you,” he said in Spanish. All my stuff was there. Chewy was not a crook.

Chewy’s Story

The following morning he took me to harvest oysters and scallops. When we returned, he started preparing fresh ceviche. He made tortillas and got so hot that he took his shirt off. I saw a deep scar going down his chest, and asked him what had happened.

He lived in Mazatlan, was part of a gang that often fought with other gangs from different parts of town. One day he was walking alone, and a rival gang surrounded him. One pulled out a knife and sunk it in his chest trying to kill him; he knew the guy. One of his lungs collapsed, yet he fought for his life and somehow managed to run away.

He made it to a hospital and miraculously survived. I asked him if he turned the guy in who tried to kill him. He said that you don’t do that. I later asked what happened to the guy. He told me that someone shot the attacker three times, killing him. I didn’t bother asking him who did it, but I have a suspicion.

Chewy believed that his survival was a miracle, he only had one lung but was alive. In his tent, I would watch him read the bible with broken reading glasses. Every night, when I said goodbye he would reply, “If God allows it, I will see you tomorrow.”

I hung out for a few days, and Chewy showed me his world, his life, asking nothing in exchange. He shared everything he had with a generosity you rarely find. I gave him a pair of reading glasses a friend had left in my camper, and other small things he could use. He never accepted any money.

The day I left, looking down the cliff, to the open lagoon Chewy told me, “This place saved my life. I would be dead now without it.” You could tell he loved his simple solitary life. We hugged goodbye, and I realized this was a man who was given a second chance in life and had become a different person.

With all the crime in Mexico rising, I can only say that I have had some of the best experiences with the local people. Mexicans have a way of life that many of us could learn from. I can only hope that it continues that way. Yes, crime is rising, but the core of the population is generous and giving. I feel fortunate to be able to share my time with them.