Paddling 2022 Safely

Words & Photos By: Luc Mehl

Illustrations: Sarah Glaser

This morning’s subzero temperatures in Alaska make it feel like a strange time to contemplate the 2022 packrafting season, but… it sounds more appealing than actually going outside!

I’m going to look back before looking forward—2021 was a mixed year of wins and losses.

Wins

There are more packrafters than ever before. More packraft safety courses, more safety and trip-planning resources on- and off-line. The American Canoe Association voted to incorporate packrafting and will begin offering instructor certification in 2022. This is a huge win! Sign up for the American Packrafting Association newsletter to stay updated on this effort. Finally, American Whitewater added ‘packraft’ as a vessel category to their accident and near-miss database. Monitoring trends and common hazards within the packraft community helps us identify what actually goes wrong.

Losses

There were four reported packraft fatalities in 2021—the most ever. I’m collecting as much information about fatalities, injuries, and close-calls, to help govern my safety messaging (more info is available at the packraft fatalities page). Based on this research, I will be paying special attention to the following themes in 2022.

Paddling 2022 Safely

Budding communities: There were packrafting fatalities in both Japan and Russia in both 2020 and 2021. How can we help budding communities “leapfrog” to higher safety standards and skip these unnecessary fatalities? As the global packrafting community grows and puts more effort into messaging, what can we do to sidestep geographical and language barriers?

Leashes: A leash (cord or strap) that connects the paddler to their boat is dangerous in moving water. This is not just a hypothetical concern, three of the four Japanese and Russian fatalities in 2020 and 2021 involved a leash on moving water.

The intention of a leash is that you can keep a hold on your equipment during a swim, which is even more relevant on remote trips. However, we can manage lost equipment much better than injured, missing, or drowned partners. Leashes in turbulent water can easily wrap around a body limb, preventing the swimmer from reaching shore. A leash must be releasable, but even a releasable leash is a safety concern.

Leash entanglement is a concern in open water too. But getting separated from a boat far from shore is so scary that I’m willing to risk leash entanglement. Three packrafting fatalities in open water might have been prevented by using a leash (Iceland, Greenland, Argentina).

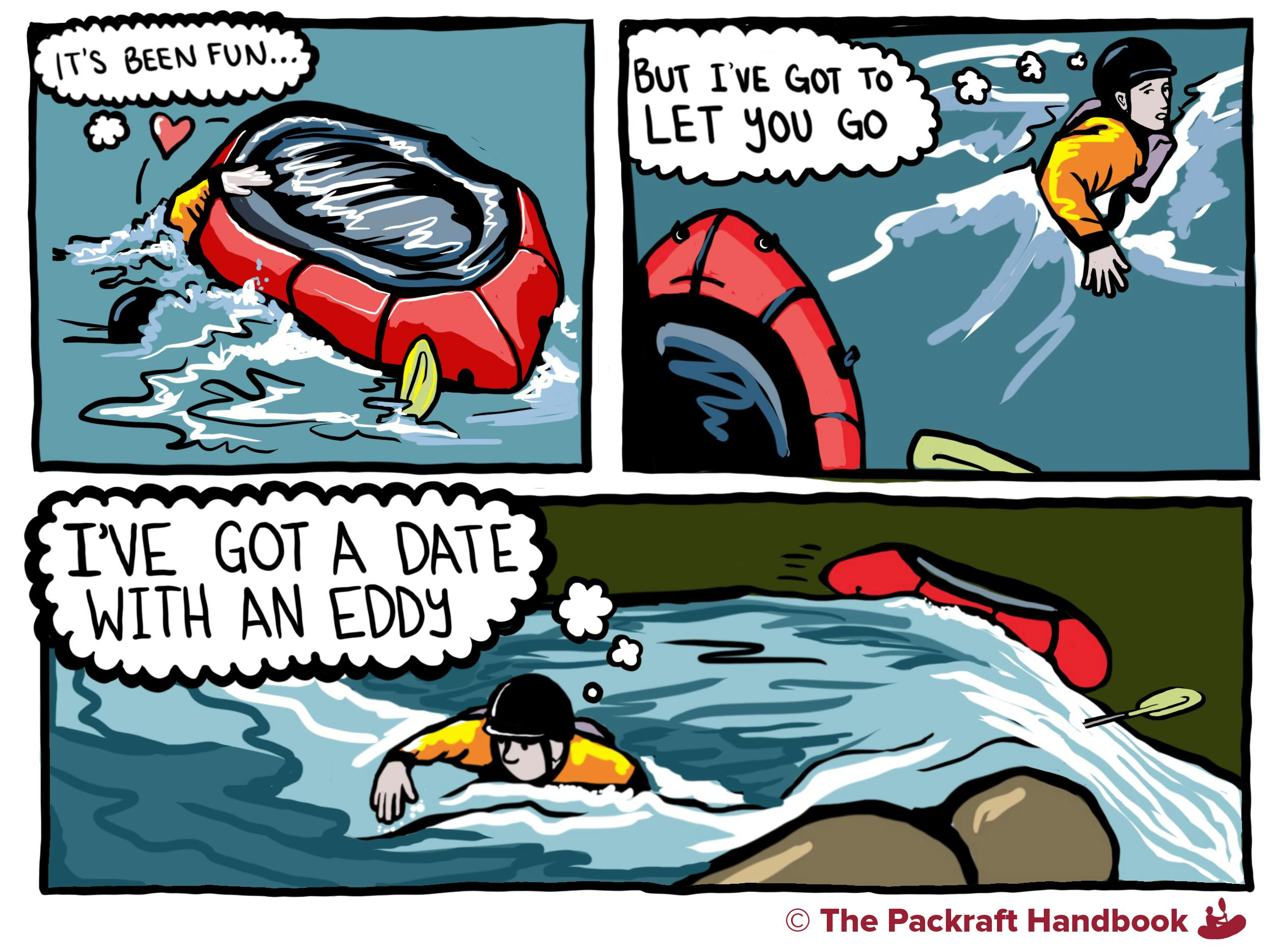

Scouting: At some level, every packraft incident on moving water could have been avoided if the paddler scouted and portaged. The decision to portage can be quite easy when a rapid is clearly difficult or dangerous—I really appreciate these ‘no-brainer’ decisions that don’t require a lot of thought. The problem is with the more subtly difficult and dangerous rapids. Two packrafting fatalities in Alaska involved portaging the hardest rapids and then getting in trouble in less difficult water. A 2021 fatality in New Zealand involved missing a critical eddy—the last opportunity to scout and portage a gorge.

Our scouting mindset should be: “Expect a river hazard around every corner.” We have the absolute best boats for portaging!

Effectively solo: The snow science community has introduced the concept of being ‘effectively solo’ in avalanche incidents. This concept applies to us too: effectively solo refers to paddlers who are part of a team, but who will not receive assistance due to their partners being out of position or lacking the skills to help. I learned this lesson while writing The Packraft Handbook. I had phrases like “paddle with partners” throughout the book, and one of the peer editors changed every “partners” to “capable partners.” The point isn’t just to paddle with other people. The point is to paddle with other people that know how to help—that can help you decide to portage, set up a throw rope, or serve as a safety boat. These are aquired skills that take intentional practice.

High water: Statistically, most paddlesport fatalities occur in Class I water. These fatalities usually occur within the first hour on the water and are often associated with improper or missing safety equipment and alcohol use. The next largest proportion of fatalities occurs in Class IV water. These paddlers generally have the right equipment and know how to use it. Class IV fatalities often have “unusual conditions,” which almost always means high water. High water was a factor in a number of packrafting incidents in 2021.

High water results in more “push.” The relationship between volume and force is exponential: twice the volume produces four times the force. It is no wonder that high water catches us off guard. Rescue crews literally have to use winches to pull pinned bodies against the current.

A new insight for me is that the repercussions of high water can last throughout the season or even multiple seasons. In the past few years, anomalous high water events in Southeast Alaska resulted in tree transport and channel scouring that completely changed the rivers. These high water conditions resulted in a fatality and Coast Guard rescue last summer. One of the paddlers told me, “I’ve jet boated that river for nine years! I counted on it being reliable.” But with high water, information from two weeks ago was no longer relevant.

In 2022, I will pay more attention to water levels, identify cut-off limits beyond which I won’t get on the water, and factor extra days on my trips so that I can wait for water levels to drop, or walk out.

Wood and other river debris: The most common factor in 2021’s fatalities and near misses was wood and other river debris. I heard from several folks that were swept under wood and thankfully resurfaced downstream. A packrafter in Japan was entrapped by a piece of scrap metal in the river.

2022 is a great year to renew your respect for wood and other river debris: work like hell to stay clear. Get off the river if you keep seeing wood hazards. Use whistles to communicate within the group if you see wood (see below).

Signaling: This is more of an observation from my instructional courses than anything else. This summer I made the predictable (but new-to-me) observation that most paddlers won’t take their eyes off of their line unless they hear a whistle. The more nervous the paddler, the more likely they will need a whistle blast to get their attention. If you are giving hand or paddle signals to someone in the water, be sure to accompany the signal with a single whistle blast.

Here’s to a happy new year full of adventure in these amazing little boats! Thanks for doing your part to build our packrafting culture of safety—a community that celebrates accomplishments, new partners, and open communication.

About the Author

Luc Mehl is an avid packrafter in Alaska and author of The Packraft Handbook.

___

Safety Courses Near You

Alpacka Raft highly recommends taking a packrafting instructional course, especially if you are new to paddlesports. All river enthusiasts, both new and experienced, can benefit from swiftwater safety instruction. Find a course near you, or plan your upcoming travel around a course in a global destination you’d like to visit! Click here to view courses.

2022 Womxn's Swiftwater Courses

Our 2022 Womxn's Swiftwater Courses with Sierra Rescue are now open! These courses will be held on March 26-27, 2022. They sell out fast, so sign up to reserve your spot today.