Two Alpacka Raft Athletes Embark on an Adventure to the Kimberley, the Furthest of Australia’s Outback, a Wild Frontier with Few Roads and Fewer People.

By Brad Meiklejohn, Alpacka Raft Legacy Ambassador. Photos by Ben Weigl, Dulkara Martig, and Meiklejohn. Follow us on Instagram all this week (Aug 13-17, 2018) to see more photos.

Dulkara’s shriek made my heart jump. The ground in front of us seemed to hop in all directions. The Cane Toads in the track were thick and freaky, baseballs and softballs that were hard to tell from rocks in the moonlight until they moved just before we stepped on them.

The toads took my attention off my feet. I wished to be off my feet but the miles to Kalumburu were not going to walk themselves. Slim hopes of a bush flight out at the Carson River Station had confronted the abandoned and overgrown airstrip. The desolate station had been no place to rest, strewn with poison 1080 dingo bait, signs warning of asbestos contamination, the sheet metal roof popping under the intense sun. The Carson River had looked so tempting, to swim, or better yet, paddle. But we couldn’t come up with an effective strategy for packrafting with crocodiles.

Our night hike was a desperate move to avoid the intense heat. The day before had nearly done us in. Cutting away from the river cross-country over stony ground through head-high spear grass under heavy packs and an Australian sun that smote like a hammer had caused a collective meltdown. I had collapsed with tingly lips, dizziness, and an overwhelming apathy, bad signs for heat stroke. We had been saved by a water hole where we lay fully clothed for two hours before heading back into the heat. Dulkara’s feet were now black and swollen, and a tinge of fear had crept into my mind. I’d been hotter, I’d gone longer and much harder, so why was I suffering so badly here in the Kimberley?

The Kimberley

The Kimberley. A single word ringing with wildness, such as the Kalahari, the Congo, the Amazon, the Arctic. The Kimberley is the furthest of Australia’s Outback, a wild frontier with few roads and fewer people. It’s a hot, hard, and remote place, home to some of the oldest rocks on the planet and an odd assortment of critters, among them lizards and plants, and possibly mammals, still new to science. I’ve made a habit of visiting these last remnants of the original planet before they get absorbed into the mundane world.

Flying over the Kimberley two weeks before I had been excited to be headed for one of the most remote corners of the world. Our timing was perfect. The Wet Season had been a good one, and the rivers were now on the drop in mid-April heading into the Dry. Clear and green from above now, the water only in the central channels, you could see how big the rivers get during the Wet, with wrack lines of trees sprawling far out into the bush.

That’s when the crocs move around, the big salties taking advantage of high water to move inland. I had laughed at the sign in the Kununarra airport saying that crocs can travel 200 km upriver during the Wet. The laughter had relieved my nerves then, but I could feel the tension returning as I looked at the reality. The Drysdale River came into view, and I was pleased to see rapids and small waterfalls pass under the airplane wing. I told myself that the salties don’t like to work to get past these croc blocks.

We swung wide over the cattle station and the plane set down on a broad grassy strip as two utes wheeled up. We were the first tourists of the season and the first packrafters they’d ever seen.

“How do those things handle the snapping handbags?” asked John puckishly as he watched us inflate our fragile-looking boats. More nervous laughter.

We all flopped fully clothed into the Drysdale River to ease the intense heat before heading downstream. Flotsam 30’ up in the trees marked the wet season high water mark, but now the Drysdale flowed along quietly over a sandy bottom amidst the paperbark and pandanus. Squawking flocks of white correllas followed us along and red-tailed black cockatoos rowed through the canopy like pterodactyls. This place felt primordial and unlike any place I had ever been. As the heat went out of the day we pulled up to a ledgy redrock camp, delighted to have made all the connections to get from Alaska to the Kimberley, at last.

On the Drysdale

For the next five days we floated the Drysdale, our merry international band of Aussies, Yanks, Kiwis, and the French Dundee. Long stretches of stillwater ended in unusual tree sieves where the water flowed straight through dense pandanus groves, emerged into splashy Class II rapids and every so often, ledgy waterfalls. While we were scouting one of these drops, a six foot “freshie” launched from a rock overhang, nearly kneecapping me as it crashed into the tailwater pool. Freshwater crocodiles, distinct by their long narrow snouts, are supposedly benign, but this one brought the croc fears straight back to my stomach.

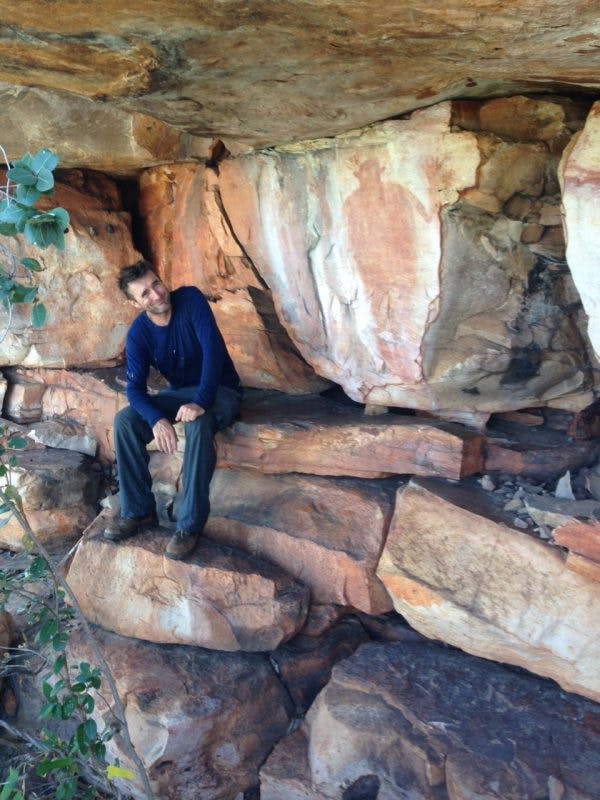

Sebastien, the French Dundee, knew the surrounding country from previous treks. He has a great memory for rock art sites throughout the Kimberley. On short hikes away from the river we felt the true heat of the day amidst the head-high speargrass and stony ground. My mind wobbled under the sun as we puzzled over the spiral rock art patterns, ancient figures with weird hairdos, and Stonehenge rock cairns. Back safely at the river, we lay fully dressed in the water waiting for our body temperatures to drop below boiling.

As the sun’s white anvil turned orange we would make camp, gather wood, and jig for bream. Fifteen degrees south of the equator the darkness comes up fast. Our fish feeds were lit by the glow of surrounding bush fires as dingoes howled at the Milky Way snaking through a jet-black sky. Hot rocks below, cool starry sky above, twelve hours until first light.

A day of alternating Drysdale flatwater lakes, tree sieves, and minor rapids ended at a major cascade that looked like runnable Class IV. Camp was just in sight along the pool below, a lovely wide sand beach backed up to a small escarpment shaded by flowering trees. The pull of shade, food, and rest overcame better judgement, resulting in a busted paddle. Our toy spare paddle didn’t look competent for the 60 kms of river remaining. But lucky for us Dulkara had brought the Golden Paddle prize along for the trip, and it was just the thing we needed. A fireside evening of McGuyver splinting, whitling, drilling, and taping created a Golden Werner hybrid with good balance and heft.

Ben’s careful itinerary had us changing rivers. The Carson River was completely unknown but promised a watershed big enough to hold a packraftable river. Before the heat came up we reluctantly said goodbye to the Drysdale and crossed over the escarpment between the two. The burn we had seen the night before had cooled, leaving blacked stony ground and easy traveling. Fourteen kilometers passed quickly enough along a route with frequent water holes. It was definitely hot, but a swim every hour made it bearable.

We found the Carson small but boatable, and full of fish. And crocs. No croc barriers lay between us and the ocean, so salties were a constant possibility. Swimming in the bigger pools was out, and you didn’t go near the water at night. The best boating plan was to group up, make ourselves appear too large for a saltie to mess with. I know how to bluff a grizzly, but trying that on a reptilian brain seemed questionable.

The pools of the Carson got longer, deeper, and more overhung. They got creepy. We nervously scanned the banks for tail drags and eyelids just above waterline. Every single freshie got a close inspection. Feeling stuck between a crack and a deep spot, we made our last camp on the Carson, facing an 80 km walk through the heat to Kalumburu.

The Final Push

The moonlit Cane Toads were the vanguard on their final push across western Australia. Introduced near Cairns in the 1930’s in an attempt to control a crop pest, the toads were the textbook experiment gone bad. The toads became a pest themselves, killing kookaburras, crocodiles, dingos, owls, and hawks as they laid a swath of destruction in their march across the Top End. Here they were at the final frontier, killing the Kimberly.

While we had found the Kimberley tough, hot, fascinating, and remote, I couldn’t call it wild. The feral cows, especially, had been heartbreaking to find all along the rivers, pooping and trampling the shady banks of the Drysdale and Carson. It was the one time I wanted most to see a croc, having a go at these hooved locust. For me, few things kill wildness as much as cows.

On our night hike to escape the brutish heat, we had to keep an eye out for the dim shadows of cows, many of which are massive, cranky bulls. The cows, the toads, the blisters and the stony miles yet to Kalumburu beat down the moonlit beauty of the Kimberley as the flowing Carson siren reminded us of the crocs that missed their chance at us.

Suffering – Teach Us What We Need to Know

Epic suffer-fests are a common badge of outdoor honor. But what exactly is suffering? My Buddhist training had taught me that suffering and pain are two different things, that pain is inevitable but suffering is optional. Our resistance to pain, our failure to accept things just as they are, is where suffering arises. We suffer when we want things to be different than they are. We suffer because we cling to pleasant experiences and push away unpleasant ones. I was suffering because I was fighting the heat, fighting the blisters, fighting the open sores worn by my pack. One of my teachers often says, “Welcome suffering, teach me what I need to know.”

Endurance is the key to suffering. Not bitter endurance, where you grit your teeth and grind your way through in misery, but patient endurance. With patient endurance we face the pain, the cold, the hunger just as they are, without trying to make them pleasant or make them go away.

My meditation practice made sense in the soft light of the cool mornings but here, flies swarming my eyes and lips, speargrass tips invading my crotch, feet swollen and bleeding, suffering was overwhelming my good intentions. The best I could do was watch each breath, and take another step towards Kalumburu.

I knew I would make it if I stopped wishing for it to end. If it wasn’t supposed to be this way, it wouldn’t be this way. There is no problem with the Kimberley. The Kimberley isn’t suffering.