Packraft Safety: How Do We Prepare for Rescue? Backcountry Ranger Monica Morin Discusses Eight Important Factors to Consider.

By Monica Morin.

The first time I threw a throw rope it landed 20 feet up in the tree behind me. Oops!! It’s rare that things ever go as planned. Being prepared for rescue can be a life saver and certainly helps expedite the clean up process when life takes that unforeseen turn.

In “Safety First: Packrafting” and “Packrafting Safety & Prep,” we went into detail about group, trip and gear selection. In “Rig to Flip Dress to Swim,” we discussed how to set up a packraft for optimal performance and to minimize entrapment hazards and loss of gear when performance ends up, well, less than optimal. We now have the boat and our trip set up for rescue, but how do we ourselves become prepared for rescue?

Strategy

Communication is the key to everything, and the put-in is a great place to review boat spacing and order, on the water communication, and expectations with your team. When there are varying skill levels in your group, it is good practice to have a strong boater in the lead and one in the back of a group (sweep) sandwiching the less experienced boaters in the middle. The leader can choose the best line, point away from obstacles with a paddle, motion for an “eddy out” if needed, and set safety at the bottom of a rapid. The sweep boater can bring first aid and assistance where needed, catch up to a swimmer or gear, or eddy out above an accident site. If your crew is large enough, the third strongest boater should go second so safety can be set on both sides of the river at the bottom of each rapid.

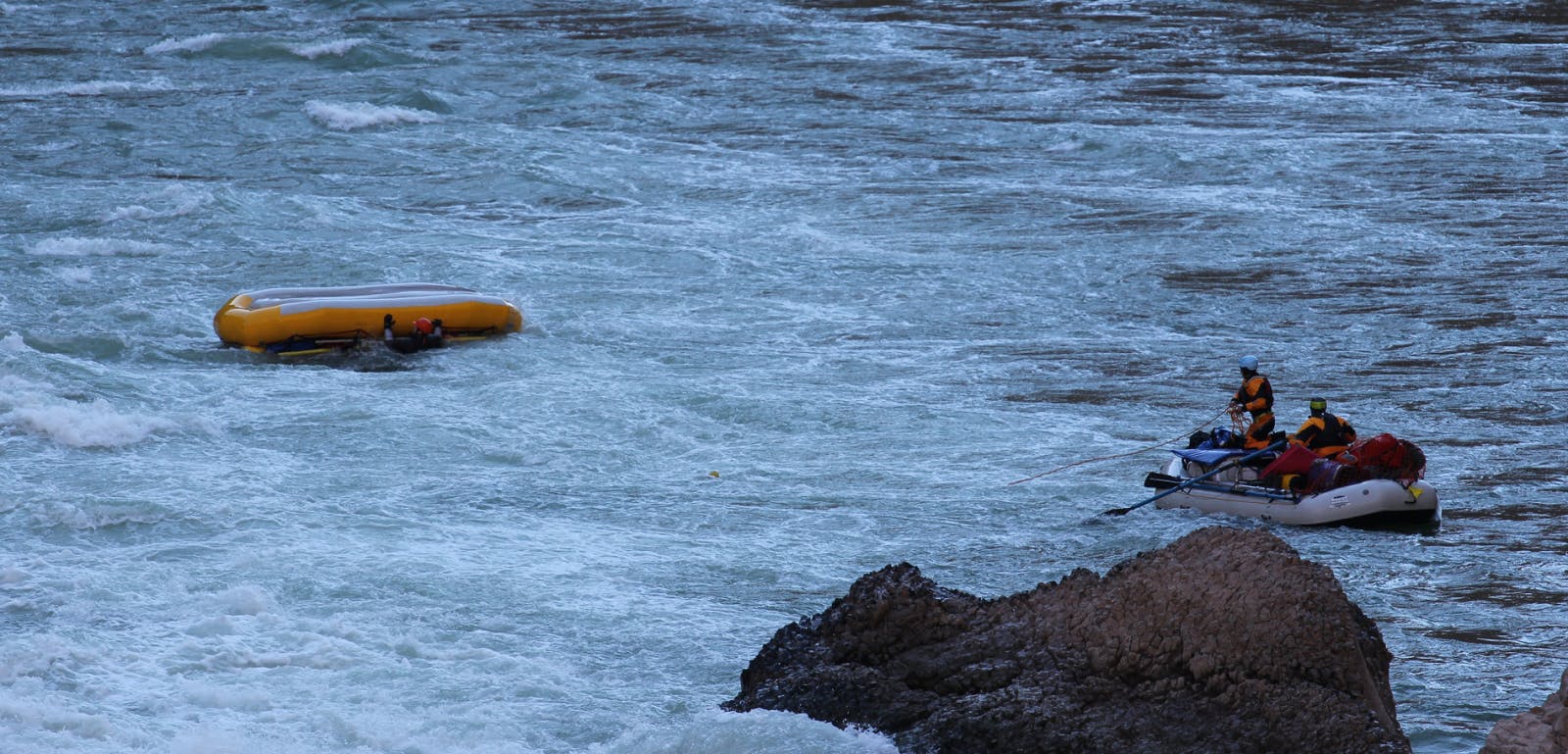

Boat spacing is especially important if an incident occurs. Typical spacing depends on the style of river. If it’s bigger volume or high water, it’s better to stay close together (within three to four boat lengths) so a swim can be cleaned up quickly before gear and swimmers are flushed away. If water is at a lower volume, give more space to allow time to eddy out if someone pins or there is a tree or other obstacle in the river. If a rapid is being run one at a time, it’s best to set safety on shore with a throw rope or have someone in a boat at the bottom who can help if there’s a swim.

Slow it Down

When I first got into whitewater, my vision was very narrow. I was so nervous my brain could only process what was directly in front of me; a classic case of tunnel vision. The more time I spent on the water, the more things started to slow down. Now, I try to look further downstream, seeing my entire line and all the others in between. I enjoy identifying eddies mid-rapid and catch them for fun. I like to know where all my partners are, where they are headed, and if there’s going to be a problem. Once the “tunnel” starts to open up, this is when you know you are ready for rescue.

Know your Limits

I still feel tunnel vision in rapids and on rivers that are pushing my skill level. I’ve been in situations where if I tried to help in a rescue I’d end up swimming myself. I felt helpless, but it’s important to recognize your limits. Synchronized swimming should be avoided. Boat in a non-remote location with a number of solid partners to establish a safer environment to push your limits. When you are paddling well within your own abilities you can become the leader for those who wish to push their skill level.

Anticipate

Once you feel ready to rescue, challenge yourself further. Become a leader. Anticipate what could happen, and put yourself in a position to do something about it if it does. For instance, eddy out below a crux or anywhere you foresee a swim. Have an idea of where you would bring a swimmer before it happens. If there is entrapment potential; eddy out where you could throw a rope or access the accident site. Think about what you would do if that scenario actually arose. If you have companions who could have trouble making the move, call an eddy out giving them an opportunity to scout or walk around. Set safety above a hazard so you could pendulum a swimmer away from it with a throw rope. If your group is of equal skill level, it’s fun to leapfrog your way down the river taking turns in lead position and setting safety in strategic eddies or on shore when needed.

Worst Case

Regardless of the class of whitewater, there is always potential for a pin or entrapment. Strainers (trees in the water) are a major factor sometimes requiring skilled maneuvering or portages to safely navigate. Foot entrapment is a looming threat even on the easiest of whitewater, and pinned equipment in a remote location could become a survival scenario not to be taken lightly.

It’s easy to leave gear at home to save weight on longer trips. Unfortunately, in an entrapment you may have less than two to four minutes to complete a complex rescue, leaving time only to use what gear you have on your person, especially if you are separated from your boat.

It’s best practice to carry in your PFD and know how to safely use two tied prusiks that will work with your rope, three locking carabiners, and anchor material. I also have a quick release belt for my throw rope so it is always on me. If you don’t have a waist belt style throw rope, make sure to grab your rope when scouting or portaging. You never know who could come floating downstream. It might also save you a trip if you decide to set shore based safety.

Depending on the trip, I also carry a pin kit in a small dry bag in my boat containing more anchor gear, pulleys, prusiks, and a folding saw. The bag protects the gear from rotting, and the saw could come in handy in some scenarios. If all of this seems foreign, a Swift Water Rescue class will cover these skills and then some. If you have yet to take formalized training, you should seriously consider it. Like a river knife, you may never need to use your rescue gear, but if you do, you’ll be happy you have it and know how to use it!

Perfect Practice Makes Perfect

It takes a lot of practice to be proficient at rescue. Even then, every scenario is different. You will be better off if you can automatically utilize your skills, which only comes with repetitive motion. A class can teach these skills, but only practice will hone them in. Go to a safe river and run bigger lines where you can challenge yourself until you or your buddy swims. Practice cleaning up the mess. Practice throwing your rope, not just once but every time you get to the put in. Once you learn how to set up systems, practice, and practice with the people you boat with. Learn everyone’s strengths, weaknesses, and natural roles as a member of a team. Work with each other to improve any weaknesses. Confidence is the key to success, and the only way to be confident is to practice.

If You See It Say It

The recent incident in Wrangell St. Elias National Park was a reminder to us all of the swift and extreme consequences our sport can have, especially for the ill prepared. So why do we take that risk? Packrafts are like the master key, opening an infinite world of possibilities for exploration, challenge both mentally and physically, and ultimate adventure. It forces us to leave the creature comforts at home in exchange for blisters, wet feet, and both real and raw experiences providing a connection to the landscape unparalleled to anything you could experience elsewhere.

Risk is involved with everything we do in life. I feel it can be appropriate to take risks, as long as one understands the consequences and mitigates them to the best of her or his abilities. We have come a long ways from the days of bike helmets and sleeping pads as PFDs, but packrafting is still in its developing stages as a sport. It is up to us, as a river community, to help educate those that may not be up to speed with the reality of the situation out there. By providing mentorship, leading by example and being both open to and willing to provide feedback for others we have been making leaps and bounds toward a solid culture of safety within the packraft community, which I am very proud to be a part of.

Seeking Further Education

The opportunity for packraft specific training is increasing exponentially. There are now packraft specific swiftwater rescue certifying courses available along with many packraft instructional courses if a certification is more than you need. The American Packraft Association (APA) has an education committee and an education page with important links to free resources, along with a forum for any questions that may arise. There are often paddler’s clubs or Facebook pages in larger communities that can be great places to find boating partners. Education is no exchange for experience, so make sure to take the proper time to develop the skills required for harder, and/or more remote trips.

About the Author: After working for public lands for eight years, bouncing between the Pacific Northwest and the Rockies as both a swift water safety educator and backcountry and river ranger, Monica Morin moved to Valdez, Alaska in 2013. She bought her first packraft to tie together her love for the river and mountains. During the winters she helped education efforts with the Alaska Avalanche Information Center. When she started working as a ranger in Denali National Park in 2014, she began to enjoy what Alaska truly had to offer and packrafted every chance she could. In the meantime she started to hear stories of serious near misses and mishaps while packrafting. She thought that a packraft awareness lecture could help improve awareness to the packraft community in the way avalanche awareness had for the ski and snow machine community. How her goal is to help promote a culture of safety within the packraft community by encouraging formal training, education, and mentorship.