Multisport Adventurer & Alaskan to Teach Packrafting Safety & Awareness Classes

If you are unable to attend these packrafting safety courses, presenter Monica Morin will be video taping them. We will share the videos once they are published. Dates for her presentations include: June 12th, 6p.m. at Beaver Sports in Fairbanks and August 1st, 6p.m. at REI Anchorage.

Many new packrafters come to the sport from a background of backpacking or adventure racing. They often run rivers in these ultralight, stable, and highly maneuverable craft that they would not have the skills to attempt in a kayak or canoe. With limited skills in reading water, hazard assessment, and ability to take advantage of river features to maneuver or scout, new packrafters can easily get into situations they are unprepared to handle. Becoming more aware of safety and skills developed in the whitewater boating community and among river professionals can help packrafters progress safely as they explore new rivers. Adventurer and packrafter Monica Morin will be delivering multiple packrafting safety & awareness presentations to help prepare packrafting enthusiasts for this upcoming season and to minimize dangerous situations. She will cover a variety of topics, including:

- Choosing the appropriate packrafting adventure for a person’s skill levels;

- Evolution of packrafting, and why the sport is growing so rapidly;

- Trip prep and planning;

- Packrafting-specific safety equipment;

- Packing tips;

- Choosing trip partners;

- Selecting routes and rivers best suited to group experience and skill level

- And much more…

We recently chatted with Monica about her experience packrafting and why she’s doing these packrafting safety presentations.

What is it about packrafting that you love? How did you get into it?

What about packrafting do I not love?! Packrafting is everything I enjoy most in life scrunched into a portable, light weight package. My unsatiated addiction to boating began in West Virginia where I raft guided and went to college. After I graduated, I volunteered as a backcountry ranger at Mount Rainier National Park, where I fell in love with the mountains. I have spent the last 12 years working in the field for public lands both on and off the river all over the west coast and in Alaska. The mountains have become my home, the place I am most comfortable. I’ve always fit in well with other backpackers. A person is rich in proportion to the things they can do without. When you can only carry with you what is on your back, life is simple and allows more time to connect with the place that you are in. Packrafting exacerbates this by challenging you to leave creature comforts at home in exchange for a more efficient and fun mode of travel. I love packrafting because it keeps things simple while combining my two passions; rivers and mountains.

Can you offer some additional details on your whitewater safety, packrafting and general paddling background and skills?

My first swift water rescue course was part of raft guide training in 2003 on the New and Lower Gauley Rivers in West Virginia. We swam big water, performed dynamic rescues, and righted plenty of flipped boats. My current safety practices and etiquette is a reflection of my initial training. It still echoes in my head, “Position yourself where you can be of assistance if a rescue is needed. Always keep your head on a swivel.” Since guide training I’ve taken at least ten Swiftwater Rescue Courses. I started to lead trainings and help out in classes last year and am currently moving more in the direction of education. I have been kayaking for about ten years and packrafting for five. In Alaska I am in a centralized location to some of the best packrafting arguably in the world. The last two winters I worked as a river ranger in Arizona. I may not be even close to a class V boater or the strongest packrafter around, but I like to think that I am a safe boater and I know my limits.

Can you explain a bit more about what you mean by “exploring how packrafting has evolved”? From your perspective, how has it evolved?

In my presentation I go over a short bit of packrafting history. Packrafts have evolved from the first inflatable watercraft invented in the mid 1800’s, to the Alpackalypse; an inflatable, packable watercraft capable of satisfying extreme whitewater enthusiasts. With the recent increase in demand packrafts have become reliable, stable, and versatile crafts. I am excited to see where technology will take us in the future.

What are some key things people should know about preparation and planning for a multi-day packraft trip, and can you explain why they are key?

My presentation is about mitigating risks before you get on the water. Either choose a trip that meets your group’s objectives or choose a group that meets the objectives of your trip. Do this by using resources available in your area (=see the below list of resources). Seek out team members with similar motivation, comfort level, and skill. Lay out expectations for the trip, communication, and safety prior to leaving the living room.

Once you have decided on a trip, make sure you leave an itinerary and map with someone who can call for assistance if you are overdue. Carrying an effective two-way form of communication is imperative to communicate your needs in the case of an emergency. Only call for help to save someone’s life, limb, or eyesight since resources in Alaska are very limited and every call places rescuers at risk. Plan to self extricate. Also, having someone on your trip with medical training along with a good med-kit can be a life saver, literally.

What are some key safety considerations for packrafters and can you explain why?

Packrafting is a gear intensive sport. In my presentation I go over all the gear you should have for a cold water trip in Alaska (see the below list). If you forget or lose any of that gear, it can be a trip ender. It is good to have a plan to hike out if gear is lost. Try and prevent losing your boat by having the right number of competent boaters to assist in a rescue. Tie up your boat when on shore in case there is wind or the water rises. Sometimes, no matter what you do, a boat can get lost. I carry my ten essentials on my person while on the river. I have a map, compass with a signaling mirror, inReach, space blanket, iodine tablets, matches and firestarter in a sil-nylon pouch stuffed down one leg of my dry suit. I always keep a few extra granola bars along with my knife inside my pfd, and I wear extra warm clothes under my dry suit. You can leave out the headlamp if it’s mid summer in Alaska.

Prior to getting on the water, you should have a plan for boat spacing, group order, and identifying possible scouting and regrouping areas. Go over standardized hand and whistle signals prior to putting on. The American Whitewater Association has a code of safety that outlines universal river signals and best practices.

Also, clearly outline expectations for the group. If you’re on a high volume river, for instance, keep within a boat length and a half from each other. That way if someone swims, you are right there for a rescue. If the river is low volume, you may need to give more space to allow for access to eddies or reaction time in case someone gets stuck or sees a tree around the corner. When boat scouting a river, always be looking for eddies you can catch before getting into any unknown terrain. If you can’t see around a corner or to the bottom of a rapid, get out and scout.

There is so much to learn. Many of these skills are best learned in a hands on course like a swiftwater rescue class geared towards packrafting. A class is no exchange for experience, so practice these skills somewhere close by before venturing off into the great unknown. Synonymous to cragging to prepare for alpine climbs, road side runs are a great way to improve your skills.

Why do you feel it’s important to teach courses like this?

I had too many friends tell me stories about lost gear and near misses on the river. A lot of these incidents involved whitewater well above the operator’s skill level, in remote locations, on rivers that were rarely run, if ever run at all. They were excited to use packrafts as a tool, a mode of transportation to cover ground and explore more territory. It was easy to look at a map and plan a route. The river simply became part of that route, a line on a map.

I like to compare packrafting to backcountry skiing. Due to the number of incidents each year, avalanche education has become standardized and well-developed. Whether motivated by steep powder or ease of travel in the mountains, if you are going to travel in avalanche terrain it is culturally encouraged to have a competent partner, carry avalanche gear, and know how to use it. For the most part, the risks are understood and decisions are taken seriously regarding the hazards involved. My goal is to help get packrafting to match these standards by encouraging formal education and mentorship.

List of Resources for Alaska Boating

Guidebooks:

- “Fast and Cold,” by Andrew Embick

- “Alaska Whitewater; a Guide to Rivers and Creeks in the Last Frontier,” by Tim Johnson

The internet:

- American Whitewater (current river events, levels, descriptions, safety code, description of river classes)

- US Gov Water Data (current river levels)

- Things to Luc At, blog by adventurer Luc Mehl (great packraft specific information)

- American Packraft Association

Locals:

- Rafting and packraft guiding companies are a great source of local information and may offer shuttle service depending on the company.

- Ask around and see if anyone has done the same trip as you, usually people are very open and willing to provide beta.

- Local paddling clubs can be a great place to meet other boaters.

List of Equipment you should bring with you for cold-water boating

- Packraft

- Paddle plus spare

- Appropriate PFD, whistle and knife

- Appropriate Helmet

- Skirt

- Inflation bag

- Optional dry bags to stow inside your boat or dry bags for your gear if strapping it to the outside of your boat

clean rigging on your boat (no loops, dangling lines, non-locking carabiners, or anything you can get entrapped in) - Patch/repair kit (know how to use it)

- Med Kit

- Dry suit

- Gloves/Poggies

- Appropriate Footwear

- Throw Rope

- Appropriate river clothing

- Communications

Depending on the trip:

- Pin Kit

- Leash, perimeter line

- Day dry bag

- Pus all your normal backpacking gear

Carry on your person:

- Map and compass with a signaling mirror

- Two-way satellite communication

- Space blanket

- Warm clothes (under your dry suit)

- Iodine tablets

- Matches and firestarter

- Extra calories

- Knife

- Headlamp if it gets dark at night

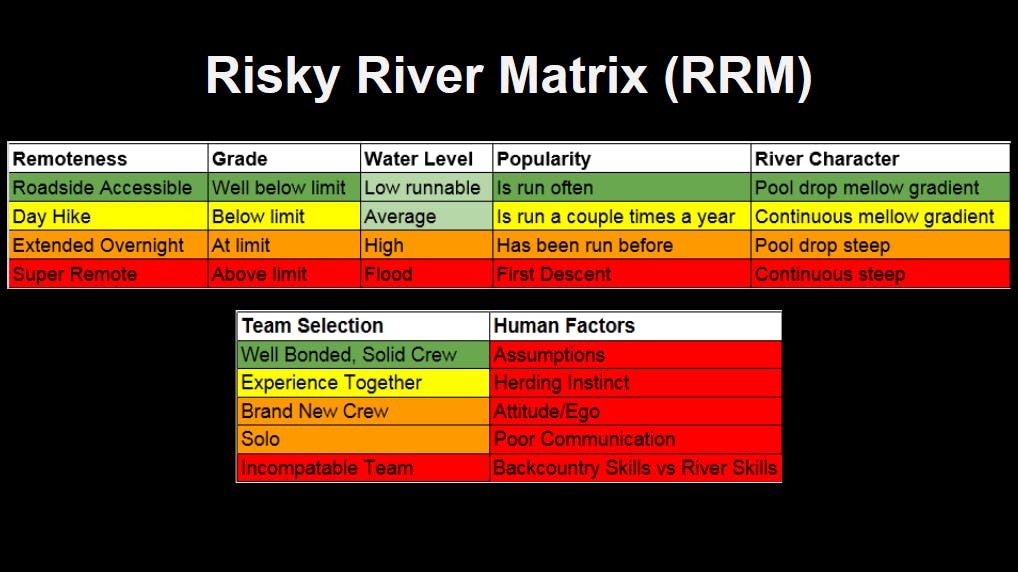

Here is a tool to help you think about what river may be appropriate for your team. Green signifies a lower risk, whereas red would mean higher risk in that category. I left “low runnable and average” in a lighter green because it depends on the river. Some rivers a low flow might actually be more dangerous than high flow.